How to write a limerick

Introduction

Mr Coe, my creative writing teacher, calls limericks ‘nonsense’ and ‘baloney’. I know what nonsense means; I have no idea what baloney means but from the way in which Mr Coe uttered the word I managed to work out that it isn’t, in Mr Coe’s opinion, something good. In any event, he devoted a small section of one of his hour long classes to limericks. He did this somewhat grudgingly.

But never mind grumpy old Mr Coe. I think limericks are brilliant. They’re short and they rhyme – what more could you want?

Mr Coe, my creative writing teacher, calls limericks ‘nonsense’ and ‘baloney’. I know what nonsense means; I have no idea what baloney means but from the way in which Mr Coe uttered the word I managed to work out that it isn’t, in Mr Coe’s opinion, something good. In any event, he devoted a small section of one of his hour long classes to limericks. He did this somewhat grudgingly.

But never mind grumpy old Mr Coe. I think limericks are brilliant. They’re short and they rhyme – what more could you want?

The limerick form

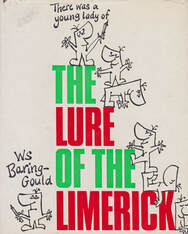

Not long after Mr Coe’s introduction to the subject, I found a useful book in the Hospice Bookshop called The Lure of the Limerick (see picture above) by somebody called W S Baring-Gould. This is full of useful information and contains lots of limericks, but some of them are quite rude (don’t worry – or don’t be too disappointed; none of the limericks below are rude).

Here is what I have learned about limericks from Mr Coe and The Lure of the Limerick:

Limericks contain five lines.

1. Line One rhymes with Line Two and Line Five

2. Line Two rhymes with Line One and Line Five

3. Line Three rhymes with Line Four

4. Line Four rhymes with Line Three

5. Line Five rhymes with Line One and Line Two

Notice how Lines One, Two and Five are all of a similar length; notice also that Lines Three and Four are similar in length to each other but shorter than the other three – I’ll come back to this in a mo.

The rhyme sequence can also be written as:

A

A

B

B

A

Or:

Hay

Hay

Bee

Bee

Hay

Each line has a certain number of beats which is the reason why Lines One, Two and Five are longer than Lines Three and Four. As W S Baring-Gould explains, ‘In most, but by no means all, limericks there are usually nine ‘beats’ in lines one, two and five; six ‘beats’ in lines three and four; the third, sixth and ninth ‘beats’ in lines one, two and five are accented: ditty-dum, ditty-dum, ditty-dum.’ Mr Baring-Gould goes on to discuss anapestic rhythm, dactyls and paeonic measure which I’m sure is fascinating but I think we have enough information to make a start.

Here’s a limerick I wrote inspired by the information I found in The Lure of the Limerick:

Line one should have beats numbered ninely;

For line two, the same scheme does finely.

For line three, six will do

And for four the same’s true.

Nine in five ends it all divinely.

Except it doesn’t really, does it? It’s stilted and lacking rhythm and flow. I think it’s because I’ve confused syllables with beats. Do you think this works better?

Line one should have beats numbered ninely;

For line two, the same scheme does just finely.

For line three, six’ll do

And for four the same’s true

Nine in five ends it all quite divinely.

Hmm. Perhaps that’s a bit better but it could probably do with a polish.

So, polish, polish, polish until it sounds just right when you read it out loud. Everything will be flowing and everything will be rhyming wonderfully; that’s what to aim for. That’s certainly what I aim for – it doesn’t always works out perfectly perfectly but that’s what I aim for.

An example

In The Lure of the Limerick there is some discussion about the search for the best limerick of all. That’s not what I’m striving for. As in all others things, I’m aiming for neatness: good rhythm, good rhyme and a satisfying final line. And here lies a problem – I struggle with the last line. My Limerick notebook is full of limericks with four lines – these are not limericks (limericks have to have five lines). I tell myself I’ll return to them to complete them at some stage. Hopefully I will.

When writing your limerick, bear in mind that the first line introduces a person or an idea; or a person and an idea. The following three lines can take the small narrative in a different (and perhaps surprising) direction. The final line has to wrap everything up neatly. And that’s where I struggle.

Here’s an example:

A spotty young man called Herbert, [okay, I’m listening]

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet. [I wasn’t expecting that. Please continue]

They made his tongue fizzy [I bet they did]

And his head very dizzy [not super-keen on the use of ‘very’]

????? [In your own time…]

So now I have a problem. You have a problem, too. You’ve just read a limerick with no neat and satisfying last line. Your problem is dependent on my problem and my problem is that I only know one word that rhymes with ‘Herbert’: ‘sherbet’. And I’ve used that at the end of the second line.

Hmm. What to do? What to do?

There are four solutions that I can think of:

Solution 1

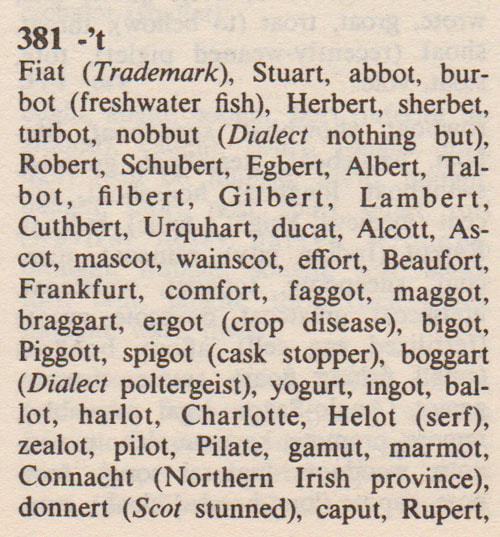

Increase your vocabulary by reading a dictionary. One of my hobbies is reading my English dictionary but I only dip in and out. There are a couple of problems with this proposal. Firstly it’ll take a long time – more time than we have here – to read the entire dictionary. The second problem is that there might only be one word (sherbet) that rhymes with Herbert. This may not be the best solution to our problem.

Solution 2

Make up a new word. This certainly has potential. I used this technique to great effect in my masterpiece of the limerick form called Redruth. Here it is:

A lisping old man from Redruth

Always struggled to tell the truth.

When asked, ‘Why mendacity?’

He replied, ‘With veracity

One should always play fast and looth!’

According to my dictionary, and as you’ll know, there is no such word as ‘looth’. Or at least there wasn’t until I invented it. It’s absolutely fine to make up new words, particularly, I think, if people will be able to guess what the new word is standing in for. Above, of course, the word ‘looth’ is used instead of ‘loose’ because it rhymes better with ‘Redruth’ and ‘truth’.

I also invented ‘anticlockwises’; not that it’s actually a ‘new’ new word; it’s a plural of a word that wouldn’t usually be pluralised. You can see how I used it here:

Devizes

There was an old man from Devizes

Who liked stories chock full of surprises.

He constantly yearned

For tales that turned

Both clockwise and anticlockwises.

So, invent new words and pluralise words that shouldn’t be pluralised.

By the way, did you know that William Shakespeare invented lots of new words? Mr Coe told us.

Here’s a limerick inspired by this:

An able young man called Will,

Wrote poems and plays with a quill.

New words like ‘well-read’,

‘Bump’ and ‘loggerhead’

Flowed out of his pen with great skill.

But, according to the internet (so it must be true) Shakespeare didn’t invent ‘looth’. I did. Ha! Take that, Mr S.

Back to Herbert and his sherbet. Can you invent a new word that rhymes with ‘Herbert’? I don’t think I can. Or rather, I can, but berbert, curbet, lerbert and so on are pretty daft words. Nonsense in limericks is fine. Limericks are nonsense, according to Mr Coe. But there needs to be some small logic contained within them. The use of ‘looth’ instead of ‘loose’ in Redruth has a certain amount of logic; we know the old man has a lisp and it’s used as a substitute in a fairly well-known saying – to play fast and loose.

It doesn’t look like inventing a new word will solve our problem.

Solution 3

Settle for repeating the word ‘Herbert’. Not ideal but it’ll work.

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head very dizzy

Poor dizzy and fizzy young Herbert.

You see? That does work. I think repeating the words ‘dizzy’ and ‘fizzy’ somehow lessens the disappointment of having to repeat ‘Herbert’. Who knows?

According to The Lure of the Limerick a man called Edward Lear was the ‘the Poet Laureate of the Limerick’. Mr Lear lived from 1812 to 1888 and he wrote lots of limericks. I introduce him here because I’ve read a few of his limericks and it is clear that he was keen on repeating one of the rhyme words from the first two lines in line five. Here’s an example:

There was a young lady from Norway

Who casually sat in a doorway;

When the door squeezed her flat,

She exclaimed ‘What of that?’

This courageous young lady of Norway.

And another:

There was a young lady of Greenwich

Whose garments were border’d with spinach;

But a large spotty calf

Bit her shawl quite in half,

Which alarmed that young lady of Greenwich.

You see what I mean. I’m in no position to criticise Mr Lear (let’s face it, my efforts are barely passable) but couldn’t he have thought of something else to rhyme with ‘Norway’ and ‘Greenwich’. Anyway, according to The Lure of the Limerick, in the olden days people absolutely lapped up Lear’s limericks, so what do I know?

Here’s a limerick I wrote inspired by Edward Lear:

A rhyming old man called Lear

Wrote limericks all wanted to hear;

Four lines worked well

But the fifth? Less swell.

That silly old man called Lear.

So, repeating the word ‘Herbert’ is a possible solution to our problem. It’s not, in my opinion, altogether ideal but pursuing this course would reflect the work of the Poet Laureate of the Limerick so it’s not entirely hopeless.

Before we plump for this resolution let’s consider one final option.

Solution 4

Consult a Rhyming Dictionary. Such a thing does exist (see picture). As you can see, I have a copy of The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary – there are probably others but I have no doubt that the Penguin one is the best. I will reach for my copy now but I can’t believe there are any other words that rhyme with Herbert…

Not long after Mr Coe’s introduction to the subject, I found a useful book in the Hospice Bookshop called The Lure of the Limerick (see picture above) by somebody called W S Baring-Gould. This is full of useful information and contains lots of limericks, but some of them are quite rude (don’t worry – or don’t be too disappointed; none of the limericks below are rude).

Here is what I have learned about limericks from Mr Coe and The Lure of the Limerick:

Limericks contain five lines.

1. Line One rhymes with Line Two and Line Five

2. Line Two rhymes with Line One and Line Five

3. Line Three rhymes with Line Four

4. Line Four rhymes with Line Three

5. Line Five rhymes with Line One and Line Two

Notice how Lines One, Two and Five are all of a similar length; notice also that Lines Three and Four are similar in length to each other but shorter than the other three – I’ll come back to this in a mo.

The rhyme sequence can also be written as:

A

A

B

B

A

Or:

Hay

Hay

Bee

Bee

Hay

Each line has a certain number of beats which is the reason why Lines One, Two and Five are longer than Lines Three and Four. As W S Baring-Gould explains, ‘In most, but by no means all, limericks there are usually nine ‘beats’ in lines one, two and five; six ‘beats’ in lines three and four; the third, sixth and ninth ‘beats’ in lines one, two and five are accented: ditty-dum, ditty-dum, ditty-dum.’ Mr Baring-Gould goes on to discuss anapestic rhythm, dactyls and paeonic measure which I’m sure is fascinating but I think we have enough information to make a start.

Here’s a limerick I wrote inspired by the information I found in The Lure of the Limerick:

Line one should have beats numbered ninely;

For line two, the same scheme does finely.

For line three, six will do

And for four the same’s true.

Nine in five ends it all divinely.

Except it doesn’t really, does it? It’s stilted and lacking rhythm and flow. I think it’s because I’ve confused syllables with beats. Do you think this works better?

Line one should have beats numbered ninely;

For line two, the same scheme does just finely.

For line three, six’ll do

And for four the same’s true

Nine in five ends it all quite divinely.

Hmm. Perhaps that’s a bit better but it could probably do with a polish.

So, polish, polish, polish until it sounds just right when you read it out loud. Everything will be flowing and everything will be rhyming wonderfully; that’s what to aim for. That’s certainly what I aim for – it doesn’t always works out perfectly perfectly but that’s what I aim for.

An example

In The Lure of the Limerick there is some discussion about the search for the best limerick of all. That’s not what I’m striving for. As in all others things, I’m aiming for neatness: good rhythm, good rhyme and a satisfying final line. And here lies a problem – I struggle with the last line. My Limerick notebook is full of limericks with four lines – these are not limericks (limericks have to have five lines). I tell myself I’ll return to them to complete them at some stage. Hopefully I will.

When writing your limerick, bear in mind that the first line introduces a person or an idea; or a person and an idea. The following three lines can take the small narrative in a different (and perhaps surprising) direction. The final line has to wrap everything up neatly. And that’s where I struggle.

Here’s an example:

A spotty young man called Herbert, [okay, I’m listening]

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet. [I wasn’t expecting that. Please continue]

They made his tongue fizzy [I bet they did]

And his head very dizzy [not super-keen on the use of ‘very’]

????? [In your own time…]

So now I have a problem. You have a problem, too. You’ve just read a limerick with no neat and satisfying last line. Your problem is dependent on my problem and my problem is that I only know one word that rhymes with ‘Herbert’: ‘sherbet’. And I’ve used that at the end of the second line.

Hmm. What to do? What to do?

There are four solutions that I can think of:

Solution 1

Increase your vocabulary by reading a dictionary. One of my hobbies is reading my English dictionary but I only dip in and out. There are a couple of problems with this proposal. Firstly it’ll take a long time – more time than we have here – to read the entire dictionary. The second problem is that there might only be one word (sherbet) that rhymes with Herbert. This may not be the best solution to our problem.

Solution 2

Make up a new word. This certainly has potential. I used this technique to great effect in my masterpiece of the limerick form called Redruth. Here it is:

A lisping old man from Redruth

Always struggled to tell the truth.

When asked, ‘Why mendacity?’

He replied, ‘With veracity

One should always play fast and looth!’

According to my dictionary, and as you’ll know, there is no such word as ‘looth’. Or at least there wasn’t until I invented it. It’s absolutely fine to make up new words, particularly, I think, if people will be able to guess what the new word is standing in for. Above, of course, the word ‘looth’ is used instead of ‘loose’ because it rhymes better with ‘Redruth’ and ‘truth’.

I also invented ‘anticlockwises’; not that it’s actually a ‘new’ new word; it’s a plural of a word that wouldn’t usually be pluralised. You can see how I used it here:

Devizes

There was an old man from Devizes

Who liked stories chock full of surprises.

He constantly yearned

For tales that turned

Both clockwise and anticlockwises.

So, invent new words and pluralise words that shouldn’t be pluralised.

By the way, did you know that William Shakespeare invented lots of new words? Mr Coe told us.

Here’s a limerick inspired by this:

An able young man called Will,

Wrote poems and plays with a quill.

New words like ‘well-read’,

‘Bump’ and ‘loggerhead’

Flowed out of his pen with great skill.

But, according to the internet (so it must be true) Shakespeare didn’t invent ‘looth’. I did. Ha! Take that, Mr S.

Back to Herbert and his sherbet. Can you invent a new word that rhymes with ‘Herbert’? I don’t think I can. Or rather, I can, but berbert, curbet, lerbert and so on are pretty daft words. Nonsense in limericks is fine. Limericks are nonsense, according to Mr Coe. But there needs to be some small logic contained within them. The use of ‘looth’ instead of ‘loose’ in Redruth has a certain amount of logic; we know the old man has a lisp and it’s used as a substitute in a fairly well-known saying – to play fast and loose.

It doesn’t look like inventing a new word will solve our problem.

Solution 3

Settle for repeating the word ‘Herbert’. Not ideal but it’ll work.

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head very dizzy

Poor dizzy and fizzy young Herbert.

You see? That does work. I think repeating the words ‘dizzy’ and ‘fizzy’ somehow lessens the disappointment of having to repeat ‘Herbert’. Who knows?

According to The Lure of the Limerick a man called Edward Lear was the ‘the Poet Laureate of the Limerick’. Mr Lear lived from 1812 to 1888 and he wrote lots of limericks. I introduce him here because I’ve read a few of his limericks and it is clear that he was keen on repeating one of the rhyme words from the first two lines in line five. Here’s an example:

There was a young lady from Norway

Who casually sat in a doorway;

When the door squeezed her flat,

She exclaimed ‘What of that?’

This courageous young lady of Norway.

And another:

There was a young lady of Greenwich

Whose garments were border’d with spinach;

But a large spotty calf

Bit her shawl quite in half,

Which alarmed that young lady of Greenwich.

You see what I mean. I’m in no position to criticise Mr Lear (let’s face it, my efforts are barely passable) but couldn’t he have thought of something else to rhyme with ‘Norway’ and ‘Greenwich’. Anyway, according to The Lure of the Limerick, in the olden days people absolutely lapped up Lear’s limericks, so what do I know?

Here’s a limerick I wrote inspired by Edward Lear:

A rhyming old man called Lear

Wrote limericks all wanted to hear;

Four lines worked well

But the fifth? Less swell.

That silly old man called Lear.

So, repeating the word ‘Herbert’ is a possible solution to our problem. It’s not, in my opinion, altogether ideal but pursuing this course would reflect the work of the Poet Laureate of the Limerick so it’s not entirely hopeless.

Before we plump for this resolution let’s consider one final option.

Solution 4

Consult a Rhyming Dictionary. Such a thing does exist (see picture). As you can see, I have a copy of The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary – there are probably others but I have no doubt that the Penguin one is the best. I will reach for my copy now but I can’t believe there are any other words that rhyme with Herbert…

Blimey! There are loads of them (see picture above. And that’s not all of them – the entry continues onto the next page). But wait a minute; do they all really rhyme with Herbert? Effort? Comfort? Can my The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary be wrong? No. They do rhyme but, to me, they don’t sound the same as Herbert. The most Herbert-like word in that list (apart from sherbet) is, I think, ‘turbot’. According to my dictionary (according to your dictionary, too, I’ll bet), a turbot is a European flatfish. Bingo! Now we have something to work with.

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head very dizzy

But he soon felt as flat as a turbot.

One last thing; can anything be done about that slightly annoying ‘very’. Let’s see.

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head dizzy whizzy,

But he soon felt as flat as a turbot.

There we are. I probably shouldn’t have started with Herbert. On the other hand, it does show that you can start with the most unpromising word and still arrive at something approaching a coherent limerick. So what’s stopping you? Get writing; have some fun and don’t worry about breaking any rules – there are no rules.

Brewer’s

And here’s a bit of history and background to limericks from Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (the best dictionary in the world). I looked first in the old 2nd edition in the Library. Here’s what that has to say on the subject:

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head very dizzy

But he soon felt as flat as a turbot.

One last thing; can anything be done about that slightly annoying ‘very’. Let’s see.

A spotty young man called Herbert,

Liked his strawberries dipped in sherbet.

They made his tongue fizzy

And his head dizzy whizzy,

But he soon felt as flat as a turbot.

There we are. I probably shouldn’t have started with Herbert. On the other hand, it does show that you can start with the most unpromising word and still arrive at something approaching a coherent limerick. So what’s stopping you? Get writing; have some fun and don’t worry about breaking any rules – there are no rules.

Brewer’s

And here’s a bit of history and background to limericks from Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (the best dictionary in the world). I looked first in the old 2nd edition in the Library. Here’s what that has to say on the subject:

This is the first I’ve ever heard of a chorus. What does the modern, 18th edition, tell us?

That explains it a little bit better.

Conclusion

Having read all this back, I can see that it’s perhaps less about how to write a limerick and more about how I write a limerick. Oh well. Hopefully you’ll find something to help you along. If you write any and would like to share them feel free to send them in via my Contact Page.

Good luck!

And finally… having made it this far, you deserve a treat. Here’s a little animation I made which you might enjoy. If nothing else, the music (Waltzinblack by The Stranglers) is brilliant.

Conclusion

Having read all this back, I can see that it’s perhaps less about how to write a limerick and more about how I write a limerick. Oh well. Hopefully you’ll find something to help you along. If you write any and would like to share them feel free to send them in via my Contact Page.

Good luck!

And finally… having made it this far, you deserve a treat. Here’s a little animation I made which you might enjoy. If nothing else, the music (Waltzinblack by The Stranglers) is brilliant.

Books used:

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E Cobham Brewer, 2nd edition, 1894

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Camilla Rockwood (editor), 18th edition, 2009

Collins Dictionary of the English Language, Patrick Hanks (editor), 1990

The Lure of the Limerick, W S Baring-Gould, 1968

The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary, Rosalind Ferguson, 1985

Back to Limericks

Books used:

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E Cobham Brewer, 2nd edition, 1894

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Camilla Rockwood (editor), 18th edition, 2009

Collins Dictionary of the English Language, Patrick Hanks (editor), 1990

The Lure of the Limerick, W S Baring-Gould, 1968

The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary, Rosalind Ferguson, 1985

Back to Limericks